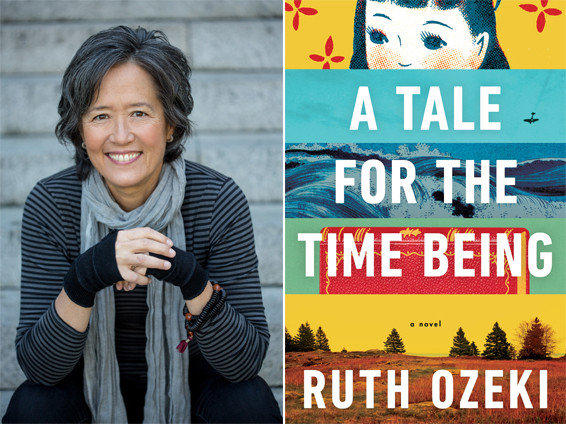

Audiobook Review of A Tale For The Time Being

Ruth Ozeki (born March 12, 1956) is a Canadian-American novelist, filmmaker and Zen Buddhist priest. She worked in commercial television and media production for over a decade and made several independent films before turning to writing fiction.

Ozeki was born and raised in New Haven, Connecticut by American father, Floyd Lounsbury and Japanese mother, Masako Yokoyama. She studied English and Asian Studies at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts and traveled extensively in Asia. She received a Japanese Ministry of Education Fellowship to do graduate work in classical Japanese literature at Nara University in Nara, Nara. During her years in Japan, she worked in Kyoto’s entertainment district as a bar hostess, studied flower arranging as well as Noh drama and mask carving, founded a language school, and taught in the English Department at Kyoto Sangyo University.

Ozeki moved to New York in 1985 and began a film career as an art director, designing sets and props for low budget horror movies. She switched to television production, and after several years directing documentary-style programs for a Japanese company, she started making her own films. Body of Correspondence (1994) won the New Visions Award at the San Francisco Film Festival and was aired on PBS. Halving the Bones (1995), an award-winning autobiographical film, tells the story of Ozeki’s journey as she brings her grandmother’s remains home from Japan. It has been screened at the Sundance Film Festival, the Museum of Modern Art, the Montreal World Film Festival, and the Margaret Mead Film Festival, among others. Ozeki’s films, now in educational distribution, are shown at universities, museums and arts venues around the world.

Ozeki has written three novels, My Year of Meats which won the Kiriyama Prize, All Over Creation

winning the American Book Award and A Tale for the Time Being shortlisted for both the Man Booker Prize as well as the National Book Critics Circle Award for fiction.

Ozeki’s meditative, era-flipping story starts with a chance discovery by a Japanese-American novelist called Ruth. Ruth lives on an island in British Columbia. Walking on the beach she stumbles on a barnacle-studded wad of plastic bags protecting a Hello Kitty lunchbox. Inside are some old letters and the diary of 16-year-old Nao (pronounced “now”) Yasutani, who describes herself as “a little wave person. Floating about on the stormy sea of life”.

By either coincidence or karma, Nao also happens to be a kind of Japanese-American, and therefore a bit like Ruth. She was born to Japanese parents, but her heart belongs to Silicon Valley, where she spent her happy formative years, and she feels just as at ease in English as Japanese. She is now back in Japan, miserable, and contemplating “dropping out of time” altogether.

Just how long has her testament been bobbing about on the waves? Is Nao a tsunami victim, or does her possible suicide predate the tragedy? The fact that Ruth is itching to know may make her decision to read Nao’s story episodically, in the on-off rhythm in which it was written (rather than to speed-read to the end and find out), feel contrived. But it gives Ozeki the chance to switch between the now of Ruth’s quietly claustrophobic life with her artist-naturalist husband Oliver and the turbulent now of Nao, whose story begins in Tokyo at the turn of the new century.

The two protagonists are chalk and cheese. Ruth’s daily life consists of Google searches, speculations about a mysterious crow, pedagogically driven information-exchanges with her husband and neighbours, internet access breakdowns and missing cats. No wonder she’s hooked on the sad soap opera of Nao’s Tokyo life.

Nao (“I’m a time being. Do you know what a time being is? It’s someone who lives in time”) may be irritating, with her constant tugging on the reader’s sleeve and her hysterical emoticons, but it’s hard not to feel sympathy for this beleaguered teenager, or to admire the power with which Ozeki evokes her plight. Nao’s father, unemployed and depressed, reads western philosophy, constructs origami insects and makes failed suicide attempts, while her mother absents herself completely: one day she’s a zonked housewife tuning out in front of aquarium jellyfish, the next she has a job in publishing. Meanwhile Nao is bullied by baroquely sadistic schoolmates: the abuse culminates in a staged funeral, a near-rape and a humiliating online knicker auction that sends her into a vortex of despair.

But thanks to the Universe, help is at hand in the form of Jiko, Nao’s ancient, anarchist-feminist great-grandmother. The tiny bald nun invites Nao to her mountain temple where fresh air and Zen wisdom work their magic. Here Nao is taught to sit straight, empty her mind, scrub old-lady skin, and offer prayers of gratitude to toilets: “As I go for a dump / I pray with all beings / That we can remove all filth and destroy / The poisons of greed, anger and foolishness.”

In an environment as fertile as this, more stories are bound to sprout, and sure enough they do. Old Jiko had a kamikaze pilot son who left secret letters – also in the Hello Kitty lunchbox – written in a code language called French. At this point Ruth, normally a keen advocate of Google’s many useful applications, seeks out Benoit, a waste disposal worker, who translates the doomed pilot’s words with the finesse of an award-winning interpreter. And finally, all – or rather a set of parallel alls – is revealed.

Seen from space, or from the vantage point of those conversant with Zen principles, A Tale for the Time Being is probably a deep and illuminating piece of work, with thoughtful things to say about the slipperiness of time. But for those positioned lower in the planet’s stratosphere, Ozeki’s novel often feels more like the great Pacific gyre it frequently evokes: a vast, churning basin of mental flotsam in which Schrödinger’s cat, quantum mechanics, Japanese funeral rituals, crow species, fetish cafes, the anatomy of barnacles, 163 footnotes and six appendices all jostle for attention. It’s an impressive amount of stuff.

One version of you might be intrigued. Another might pray it doesn’t land on your shore.- Liz Jensen, The Guardian

Ruth Ozeki does a fine job narrating A Tale for the Time Being, with an average ratiing of 4.4 out of 5 from Audible listeners. This is somewhat unexpected as many authors make poor narrators. The audio book is 14 hrs and 48 mins long.

Watch Canongate TV’s interview with Ruth Ozeki about writing “A Tale for the Time Being” on YouTube.

>